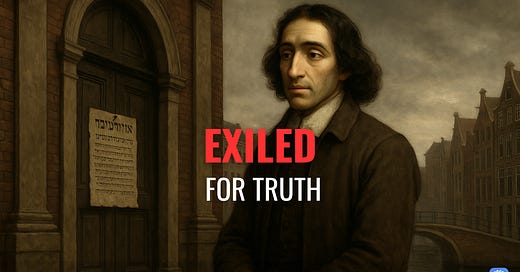

Exiled for Truth: What a 17th-Century Heretic Can Teach You About Mental Freedom

Misunderstood. Banished. Silenced. But not wrong. The forgotten clarity of Spinoza’s philosophy still speaks to those who seek mental freedom today.

For creators and thinkers who’ve ever felt exiled for seeing things differently, this is your story.

Baruch Spinoza wasn’t punished for being wrong. He was punished for thinking too clearly in a world that preferred confusion. His clarity still challenges us to question, refine, and rebuild.

I. The Excommunication That Echoed Across Enlightenment Europe

On July 27, 1656, in the heart of Amsterdam's bustling Jewish quarter, an extraordinary and brutal decree was read aloud before the congregation of the Talmud Torah synagogue.

The words were not merely formal—they were thunderous and final. Baruch Spinoza, a 23-year-old merchant’s son and promising scholar, was to be expelled, excommunicated, and cursed in perpetuity. “With the judgment of the angels and with the command of the saints,” the rabbis declared, “we ban, expel, curse, and damn Baruch de Espinoza.”

This wasn’t a routine disciplinary act. The herem—a form of spiritual and social ostracism used in Jewish communities—was rarely carried out with such venom. Nor was it ever reversed.

The writ severed all ties: Spinoza was forbidden from entering any synagogue, speaking to any Jew, or being within four cubits of a member of the community. What’s more, the edict was unusually vague. It cited “abominable heresies” and “monstrous deeds,” but listed no specific charges.

To understand the gravity of this moment, one must first grasp the precarious status of Amsterdam’s Sephardic Jews in the mid-17th century. Most had fled Iberia, victims of the Inquisition, forced conversions, and centuries of persecution.

They found a fragile sanctuary in the relatively tolerant Dutch Republic—but it came at a price. That price was self-policing.

To maintain their protected status, Jewish leaders in Amsterdam worked to suppress internal dissent that might attract Christian scrutiny. Radical ideas—especially anything that seemed to challenge Biblical authority or undermine belief in divine providence—could be seen as existential threats.

Spinoza, by that point, had quietly become such a threat.

He had been raised within the very institution that excommunicated him. He studied at the Etz Chaim yeshiva, mastered Hebrew, and delved deeply into Jewish philosophy.

But by his early twenties, he had begun to question the literal truth of scripture and the idea of a personal, anthropomorphic God.

Drawing from Descartes, the Stoics, and Maimonides, Spinoza privately argued that God was not a being who intervened in history, but the underlying substance of reality itself—boundless, rational, and impersonal. To traditionalists, this was theological dynamite.

More dangerously, Spinoza began to speak these ideas aloud—not with the firebrand rhetoric of a zealot, but with the calm logic of someone who believed truth should not be feared.

He debated rabbis, challenged received interpretations of the Torah, and even began using reason to question the afterlife and the immortality of the soul. His critics feared that such ideas could fracture an already vulnerable community and provide ammunition to Christian theologians who doubted Jewish orthodoxy.

While no official record names the individuals who pushed hardest for his excommunication, historical research points to the likely involvement of Isaac Aboab da Fonseca, a leading rabbinic authority and respected kabbalist, along with the parnassian—the lay leaders responsible for protecting the community’s legal status within Dutch society.

Their motives were not merely theological; they were deeply political. By purging Spinoza, they signalled to Dutch authorities that Amsterdam’s Jews would not tolerate internal heresy.

Spinoza himself never publicly contested the ban.

He didn’t return to plead his case. Instead, he left the Jewish quarter, changed his name from “Baruch” to its Latin equivalent, “Benedictus,” and withdrew from communal life. His only comment came in a later letter, where he wrote, “I am not unaware that I have been driven from my people.”

What makes this episode so consequential is not simply the injustice of his expulsion, but the misunderstanding that triggered it.

Spinoza was no atheist—not in the modern sense. He believed deeply in God, but not the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. He believed in a divine order manifesting reason, nature, and necessity.

This was not heresy out of rebellion; it was metaphysics born from clarity. But to a world steeped in literalism and fear, it was indistinguishable from blasphemy.

II. The Making of Baruch Spinoza

Baruch Spinoza was born on November 24, 1632, in Amsterdam’s Vlooienburg district, a reclaimed island just south of the bustling Jewish quarter. His parents, Miguel and Hanna, were Portuguese conversos—Jews forced to convert to Catholicism under the Inquisition who later fled Iberia to reclaim their faith openly in the more tolerant Dutch Republic.

Like many of their peers, the Spinozas sought safety in Amsterdam’s burgeoning Sephardic community, which had become one of Europe's most culturally and intellectually vibrant Jewish centers.

Amsterdam in the mid-17th century was a unique crucible. The Dutch Republic was a rare experiment in republican governance, freedom of conscience, and capitalist enterprise. It tolerated a level of religious diversity almost unknown elsewhere in Europe, but it was also a fragile balancing act.

The Dutch authorities permitted the Jewish community to practice openly only so long as it policed its own and remained politically quiet. The Portuguese-Jewish leadership enforced strict religious orthodoxy and social cohesion within this environment—an uneasy blend of spiritual revivalism and strategic conformity.

Spinoza came of age within this context of post-Inquisitorial rigour and intellectual rebirth. He studied at the Talmud Torah yeshiva, where he learned Hebrew, Jewish law (halakha), and medieval philosophical texts—particularly the works of Maimonides, who had tried to reconcile faith and reason earlier.

By all accounts, Spinoza was a gifted student. Yet even among such luminaries, Spinoza began to pull away—not because of defiance, but due to an insatiable drive to understand the nature of truth itself.

As a teenager, Spinoza began reading texts that would quietly shift his worldview.

The Latin works of Descartes, which circulated widely in Amsterdam, introduced him to a new mode of thinking—methodical, skeptical, and rooted in the clarity of reason. He became intrigued by the idea that truth could be derived not from revelation but from logic and deductive clarity, similar to mathematics.

But it wasn’t just European rationalism that shaped him. Spinoza also absorbed the radical writings of thinkers like Thomas Hobbes, whose secular approach to political authority questioned divine-right monarchies and the religious basis of law.

These influences didn’t turn Spinoza away from his Jewish heritage so much as they compelled him to reframe it. He began to suspect that the Bible was not the literal word of God, but a collection of historical documents—written, edited, and compiled by human hands.

Still, Spinoza was not a firebrand. He did not storm the synagogue or mock the faithful.

His calm and quiet clarity made him dangerous to the religious authorities. He asked the kind of questions that could not easily be shouted down. Such questions, spoken softly and without malice, cut deeper than heresy shouted from the rooftops.

Around the age of 20, Spinoza began distancing himself from communal life. He stopped attending synagogue regularly, adopted the Latinized name “Benedictus,” and joined a group of freethinkers interested in natural philosophy, optics, and metaphysics.

He supported himself modestly as a lens grinder, a delicate trade that would eventually lead to his early death from lung illness.

In these years, Spinoza drafted his early metaphysical treatises and began articulating his vision of a rational, deterministic universe in which God and Nature were one and the same.

While he hadn’t published anything, word of his views began circulating. The Amsterdam Jewish leadership, trying to maintain credibility with Dutch officials and fearful of Christian retaliation, saw a looming danger in the young philosopher.

Spinoza’s journey from gifted student to exiled thinker was less an act of rebellion than a slow and deliberate shedding of illusions. He wasn’t trying to destroy belief. He was trying to clarify it—to anchor the divine not in superstition or scripture, but in reality.

III. Context: 17th-Century Europe and the Rise of Fearful Orthodoxy

To fully understand why Baruch Spinoza was so swiftly and harshly excommunicated—and why his work was later banned across Europe—it is necessary to situate his ideas within the volatile context of 17th-century religious politics.

This was a century marked by both intellectual awakening and ideological terror. While the Dutch Republic offered greater tolerance than most of Europe, it remained a powder keg of competing orthodoxies, fragile alliances, and latent fears.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Mindset Rebuild to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.